Making 3D Printed Implants for Children with Ear Deformities

Over 100,000 children enter the Royal Hospital for Sick Children annually. Located in Edinburgh, its facilities attend to children like Ellie, who suffers from a congenital malformation of the ear’s elastic cartilage. Doctors call this “microtia,” a medical term that translates from Latin as “abnormal smallness of the ear.” For some with this condition, the pinna (or external ear) can be so small as to appear practically non-existent. And due to the underdevelopment of both the middle ear and external canal, microtia is o en accompanied by some level of hearing impairment. One out of every 6,000 babies are born with this condition.

Fortunately, Edinburgh is home to Ken Stewart, who heads the local Ear Reconstruction Service of Scotland. There he has been fine-tuning ways to perform reconstructive surgery on both children and adults afflicted with ear malformations.

For years, Ken had employed a number of techniques for approximating the varying circuitous designs of his patients’ ears. The most popular method is to borrow cartilage from the patients ribs and to carve this into an ear shape. In 2014, he began investigating 3D imaging solutions in an effort to streamline the pre-operative procedure for ear reconstructions. Ken admits, “With all the technology around us we need[ed] to improve this workflow.” Though Lothian NHS, where Ken is based, had already been using 3D imaging systems to design prosthetic limbs and carry out medical examinations, they wanted to improve the details of their reconstructed ears.

It was then that Ken turned to Patrick Thorn & Co., Artec’s UK gold partner. Drawing from his extensive experience with designing and re-designing ear prosthetics and implants, Ken remained skeptical that Artec’s state-of-the-art scanners could effectively 3D render the human ear. To prove to Ken otherwise, Patrick decided to produce a range of sample replicas to demonstrate Artec’s high-resolution imaging capabilities. Patrick arranged to have the ears of his neighbors and grandson scanned. Following a few imaging modifications with the help of Leios Elaborations Scanning So ware from EGS, he ordered the samples printed on the Roland ARM-10 3D Printer.

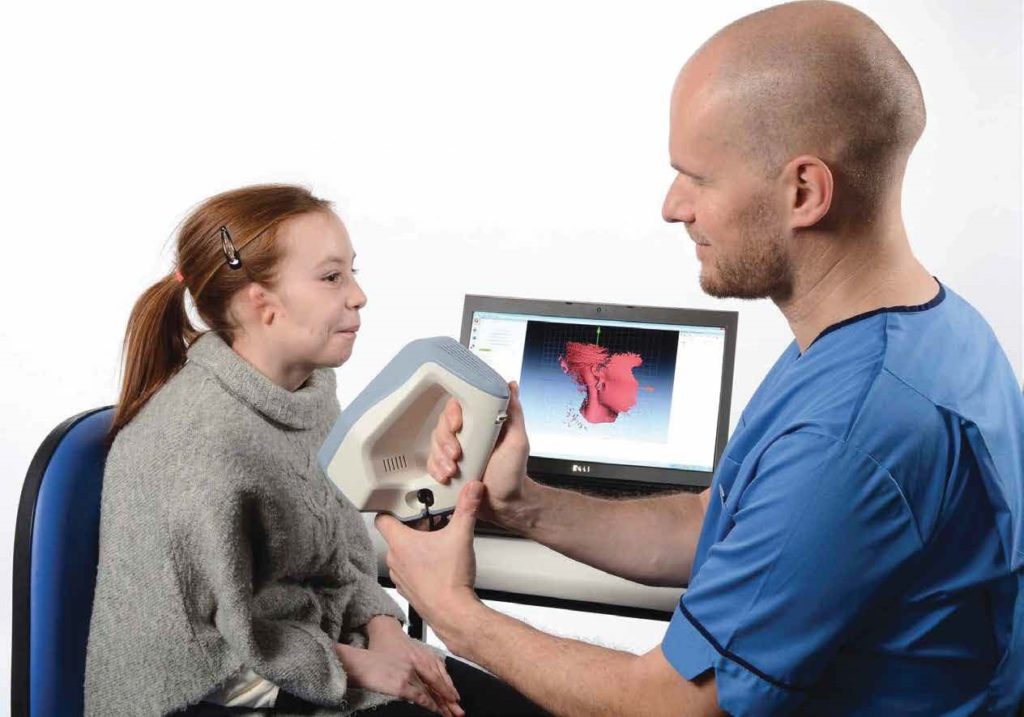

Thrilled by the results, Ken and his team knew that they had to have an Artec Spider – a high-resolution 3D scanner that is well-suited for capturing images of deeper surfaces within the ear canal as well as around the area between the ear and the head.

With the successful fundraising efforts of the Sick Kids Friends Foundation, The Royal Hospital for Sick Children purchased an Artec Spider, with Artec Studio and the Roland ARM-10. In a single afernoon, it was installed, and on the next day, hands-on training followed. Ken remarks, “With the training and additional notes Patrick provided, we can now use the solution from scanning to 3D print with relative ease. The model is then sterilized and utilized in theater to improve the accuracy of our surgical reconstruction”.

Integrating Artec Spider into Ken’s ear reconstruction practice has both simplified and systemized the ear-building process. Once the initial consultation with patients concludes, they return to the hospital to have their unaffected ear scanned. In Ellie’s case, because she was diagnosed with bilateral microtia (meaning both ears are affected), the ear of her sister, who does not suffer from microtia, was scanned instead.

Sometimes an image of the affected ear is also taken for reference. During the scanning, Artec Spider gets to work on capturing in striking detail the complex structure of the outer ear, and then probes deep into the ear canal, collecting further, invaluable visual data. A erwards, the images are uploaded into Artec Studio, where they are swi ly aligned, and fused to construct an impressive 3D digital model of the ear.

During the retouching stage, Leios is used to check the ear’s surface, remove any unnecessary elements, and allow for skin thickness by applying an internal offset. Once all the structural and cosmetic alterations have been finalized, the resulting image is mirrored. Therea er, an electronic file containing the images is delivered via a shared drive to a laboratory and loaded onto the Roland MonoFab Printing So ware, in which alignments are performed. All that’s le is to press “Go” to start 3D printing.

They are then sterilized, sealed, and sent to the operating room to serve as 3D templates for ear reconstruction.

With the help of advanced imaging solutions from Artec 3D, surgeons like Ken can rest assured that they’ll never have to approximate models for the prosthetics and implants they create.

Special thanks to Ellie and her mum for allowing us to share this success story.

This content was originally written by Artec 3D